Health managers will have to hone new skills to ensure employee engagement and high-performance in a new post-partnership era writes Gerald Flynn.

TWO decades of ‘social partnership’ were effectively killed off by the fall-out of the economic depression. The tripartite ‘Towards 2016’ social pact arrangements stumbled on for most of 2009 until finally collapsing in the days running up to last December’s Budget.

Health sector managers face a choice of reverting to the pre-partnership command and control management style or developing new competencies in communications to convince employees of the need for change. Despite Exchequer pressures and budgetary constraints, the next three years could be an opportunity to break free from the worst aspects of centralised national programmes.

These included a general expectation of pay for change; a reluctance to embrace performance management and direct employee engagement; protracted discussion and pilot programmes for even modest efficiencies; outsourcing of organisational strategic decision-making and workplace communications to trades unions ill-equipped for the task.

Managers face a choice of reverting to the pre-partnership command and control management style or developing new competencies in communications to convince employees of the need for change

In effect many managers had to abdicate their leadership responsibilities so as not to inhibit the ever expanding tentacles of national social partnership. The result was a corporatist or centrally controlled maze of partnership committees and reviews and then the inevitable recourse to the Labour Relations Commission and Labour Court.

Flexible responses

This was in sharp contrast to the flexibility and responsiveness displayed by the better managed foreign and Irish-owned manufacturing and service companies for whom external third-party intervention in employment relations is often considered a management failure.

The contrast is not a criticism of individual public sector managers but a reflection of the structural dispositions where at least four out of five health sector employees is a union member compared to a private sector density of one in five. This imbalance was a contributory factor to the heightened public-private sector divide and tensions, partly fuelled by some public service union leaders, which became more intense in the second half of 2009.

To some extent it was a tactic of victimhood so that public sector members could see that their only defenders were their respective unions. It led to the hyperbolic assertion of a Congress leader that public sector employees would rather admit that their grandparents had been ‘Black and Tans’ than reveal that they worked in education, health or local government!

In effect many managers had to abdicate their leadership responsibilities so as not to inhibit the ever expanding tentacles of national social partnership

In this journal last September, before the industrial relations climate deteriorated to its current level, HMI president, Denis Doherty cautioned against repeating the lose-lose scenarios adopted in the past. It is time for health mangers to promote flexibility and what is loosely styled as ‘modernisation,’ inspired by the managers of Irish subsidiaries of global organisations. They have to compete for resources and investment and when an overseas senior management or board decide on expansion or job cuts they get on with it.

There is little scope for complaints about how unfair the markets are and trade unions in the private sector often show adaptability and realistic responses to changed circumstances such as the fall-out of a merger or some other overseas subsidiary securing hoped for investment. Of course the health sector often has to deal with the additional burden of political direction and shifting policy priorities.

Chorus of anguish

Likewise in the health sector, there is little point in managers joining in the chorus of anguish over reduced budgets and cuts in net earnings. Instead they need to tap into the realism of many health sector employees that the public finances are in crisis, mainly due to the hubris of those in financial, property and government senior circles.

The cat is well and truly out of the bag since public service unions detailed the changes and efficiencies which they envisaged could provide savings of over €1,000m a year. The tax-payers will not tolerate attempts to squeeze that particular genie back into a partnership bottle.

The ‘Croke Park’ proposed agreement, currently being voted on by public sector union members, has proved a challenge for astute union leaders to ‘sell’ it. The next challenge will be for health managers to ‘implement’ it. This provides an opportunity for strategic management of expectations and performance norms which could be kick-started in many health service workplaces by really implementing the innovative people management training initiative for line managers developed last year by the HSE-Employers’ Agency.

From our experience in most voluntary and health agency organisations this management training often needs to be adapted to the culture and vision of each institution. Tied-in with best people management practices developed by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD Ireland), it is a powerful tool in developing employee engagement as well as enhancing high-performance and reinforcing the organisation’s values.

The post-partnership era will require much more strategic human resource management rather than the fire-fighting and crisis management

This transformation will not come from OECD reviews or management consultancy reports. It has to be built on the ground with employee buy-in and that can only be achieved in a climate of honest and competent people management.

Future concerns

The post-partnership era will require much more strategic human resource management rather than the fire-fighting and crisis management which has distracted so many health service managers in recent years.

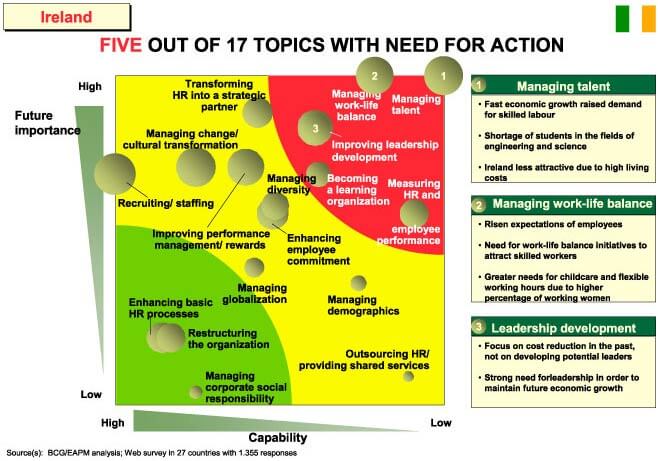

There is also a growing congruence between the HRM concerns of large firms and public sector organisations as evidenced by a major piece of research conducted by the European Association for Personnel Management.

In Ireland’s case it found that the most important concerns of senior HR directors in Ireland, reflecting issues of future importance and low current capability, were:

- Managing talent – a shortage of highly skilled people and growing competition from other states which have lower living costs.

- Managing work-life balance – adaptability needed to secure and retain key staff as part of human resource planning.

- Leadership development – there has been a focus on cost reduction at the expense of developing potential leaders and it is increasingly difficult to get top management talent.

- Measuring HR and performance – improved HR efficiency and clear contribution to organisational aims needs to be addressed.

These will be familiar problems which have also been faced in the health sector by senior management. These issues cannot be addressed through some national forum but are the responsibility of individual institutions, health areas and specific service providers.

The issue of change management and employee engagement was discussed at a recent CIPD-Ireland HR Leaders’ Seminar for health sector HR directors.

After five years of settling in the HSE and over 20 years of growing partnership structures, we may be on the brink of a new breakthrough where more capable and daring managers are willing and able to help shape the future of the health sector.

Gerald Flynn is an employment specialist with Align Management Solutions and adviser to CIPD Ireland. gflynn@alignmanagement.net. Previously he was industrial correspondent with Independent Newspapers group. http://ie.linkedin.com/in/geraldflynn